Light is an important tool for probing biology. But when pushing the limits of size and speed, optical physics poses some illumination challenges.

Optical instruments are important in all branches of life sciences, including cell biology (microscopes), biochemistry (spectrophotometers), clinical diagnostics (colorimetric assays), and molecular biology (PCR and DNA sequencers). From the most primitive candle-powered microscope to today’s high-throughput sequencers, their working principle is almost always the same: place a specimen where illumination and detection systems meet.

Detection systems get most of the attention. High-magnification lenses and ultra-efficient sensors can dominate the cost of an instrument. Innovation in detection has steadily made small gains in optical resolution and quantum efficiency, powering the modern era of microscopy to a Nobel Prize and beyond.

But the illumination system is also indispensable. Applications as diverse as monitoring cells in a fly embryo, outsmarting the physical limits of optical resolution, or witnessing the activation of a single T-cell have employed clever ways of illuminating biological specimens.

In optical instruments, all data starts as light. Once light is collected, computational resources are virtually limitless. But capturing large streams of data requires compressing a large amount of light into a small space. The associated challenges limit the performance of many high-throughput instruments.

The Solar Concentration Problem

Despite years working with microscopes, it was a project in solar energy that truly taught me about concentrating light. They are not typically found on homeowners’ roofs, but researchers have explored concentrating photovoltaics (CPV) in one form or another for decades. In CPV, mirrors or lenses concentrate sunlight onto high-performance but expensive photovoltaic cells, theoretically decreasing the cost so that 100+ MW installations become cost-competitive. But the sun changes angle in two dimensions: throughout the day and the year. If you average all positions, CPV elements must capture a broad cone of light – a “solid angle”.

This severely limits how much light can be concentrated. Stationary CPV panels cannot be designed for both high concentration and a broad solid angle: it’s one or the other. So all viable CPV strategies need to track the sun in some way. Hydraulics tilt parabolic mirrors toward the sun, for example. In our approach at Glint Photonics, a film in the panel itself self-aligned to do virtually the same thing. This meant our CPV solution approached the performance of standard silicon panels, but at lower projected cost in large-scale installations.

Brightness Conservation

The same underlying physics apply to microscopes. Starting with a source of light, two quantities can decrease but not increase in an optical illumination system: power and spectral brightness.

Power conservation is intuitive to most engineers. If a lamp or the sun generate a beam of light, the total power of the beam can only decrease as it passes through lenses, filters, apertures, and other optical components.

But conservation of spectral brightness is a less familiar concept. All sources produce light with nonzero area and divergence angle. In a light path that loses no power, area and angle can trade off. But combined, they can only increase, not decrease.

Exactly what does “combined” imply? In an idealized two-dimensional system, this is simply beam width (a) times divergence angle (theta, always positive), called the LaGrange invariant. So if an optical system (e.g. a lens) decreases a beam’s angle from state 1 to state 2, its area must increase:

Three-dimensional systems are conceptually the same but mathematically trickier: it is the “étendue”, the integral of beam area (A) and solid angle (omega) projected along its propagation direction. The same trade-off between beam cross-section and solid angle apply between states 1 and 2:

A practical example: the sun is huge, but it is also far away, so it reaches earth with an angle of only about one degree. Sid tortures Woody with a magnifying glass by focusing an image of the sun. But étendue cannot decrease, so the focused beam’s angle is much larger and therefore its focal depth is small. This means that, if Woody weren’t code-bound to remain still, he could escape the beam by moving his head toward the lens and hence out of its focus. And if Woody were to run away, Sid could not do the same damage from a long distance.

Brightness, or radiance, is the quantity that is actually conserved. It is a beam’s total power divided by its étendue. Its units are therefore power divided by (area times solid angle). Spectral brightness is the same concept but a wavelength spectrum. Its unit is the same but divided by wavelength (nm), such that brightness is the wavelength integral of spectral brightness.

So by the same principle, no lenses can focus the sun to a spot that is brighter than the sun itself. Whether a light source is the sun, a candle, lamp, LED, or whatever, spectral brightness is a characteristic of the source, and no amount of optical engineering can increase it.

This is a major barrier to collecting light from far-away stars, so astronomers perhaps know the most about spectral brightness. My thanks to Prof. Tom Kirkman at College of Saint Benedict & Saint John’s University for excellent lecture notes on the topic. While I myself have only flipped through it, Nonimaging Optics (Winston, Miñano, Benítez, and Winston 2005) is the authoritative book on étendue and its applications in collection optics.

Selecting a Light Source

Let’s return from the astronomical back to the microscopic. Modern microscopes are powered by lamps, LEDs, lasers, or exotic hybrids of these general devices. Because light sources set an upper limit on brightness, lasers are frequently the clear winner: in the visible spectrum (400-700 nm), solid-state lasers emit from a die that is 10-100 μm across, and the emitter’s shape usually means that light is highly directed. So even though a laser’s total power may be lower than that of a LED or lamp, its beam is both narrower and less divergent, so its spectral brightness can be much higher.

There are, however, other types of sources that are specifically tailored for high brightness in niche applications, such as where broadband emission is desirable or lasers’ coherence is detrimental to illumination uniformity. These include broadband plasma and laser-driven light sources.

The Cost of Flexibility

When it comes to conveying blindingly bright lasers to hard-to-reach places, fiber optics are amazing. But in reality, random bends lose the directional purity of collimated beams, which exits the fiber as a cone determined by the fiber’s numerical aperture. This, plus inevitable transmission losses, reduce the practical brightness in illumination systems supplied by fiber optics.

Free-space beams are usually better where brightness is at a premium: properly collimated beams show negligible loss and divergence in open air. But this demands more creativity in delivering beams from lasers to condensing lenses.

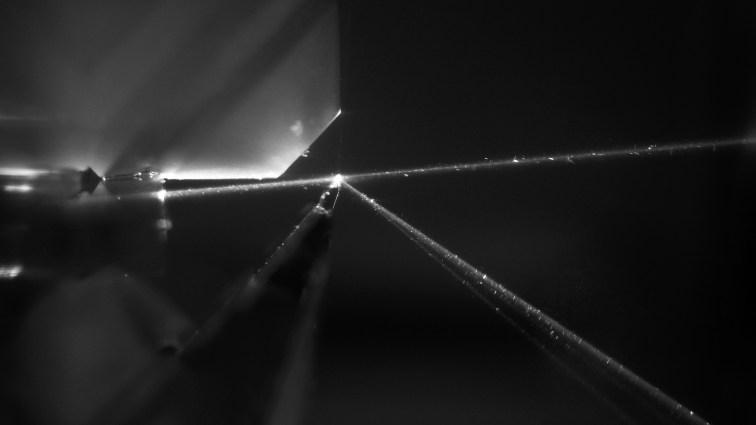

During my doctoral work, a few colleagues and I shared a common microscope for single-molecule superresolution imaging and fluorescence spectroscopy. This required us to steer the beam from a table-mounted laser, via about six mirrors, into the microscope body. This made it tedious to maintain alignment and swap in new components.

Today, laser modules are brighter, smaller, cheaper, and available in more wavelengths. In a recent instrumentation project, this has allowed me to actually move the source inside of the optical assembly, reducing meters of optical path and the tedium of aligning so many mirrors. I have also used 3d printing to squeeze condensing optics into a much smaller, lighter package. The end result is a remarkably compact high-intensity illumination system that is low-maintenance and, we hope, field-deployable without the need for routine alignment by an engineer.

Symmetry and Scanning

Solid-state laser beams are rarely symmetric. More commonly, they are elliptical with a substantial difference between long and short dimensions. Cameras have an intrinsic fast and slow scan program, either CMOS single-pixel readouts or column transfers. And most modern biophotonic instruments – confocal microscopes, slide scanners, plate readers, and sequencers – execute a program that has a fast and slow direction.

In cases like these, where illumination and detection and both asymmetric, tightly focusing one axis is more useful than focusing the other. At the limit, conservation of spectral brightness means that focusing the second axis provides no net benefit in illumination intensity.

For example, both raster and line-scan strategies can be used to illuminate a sample while projecting its image onto a camera sensor array. If exposure is limited by the power of the illumination source, it is tempting to conclude that scanning a single-pixel spot back and forth maximizes each pixel’s illumination intensity. But when the desired spot intensity violates conservation of spectral brightness, a less focused beam, such as a line, is just as intense. Scanning a line is mechanically simpler and allows parallel readout of many pixels, so careful consideration of spectral brightness makes this a win-win engineering solution.

Speckles

Lasers are coherent sources, meaning emission can interfere constructively and destructively in the beam path. One consequence is that using lenses to expand a laser beam – in one dimension or two – expands random points of interference, such that the projected beam has speckles, fringes, and other inhomogeneities. Sometimes, these are not consequential for data interpretation, such as applications where the entire beam is ultimately integrated into a single pixel, or where postprocessing can correct for predictable speckle patterns. But in other cases, especially where intensity and beam focus are critical, these may irrecoverably mask features in microscope images.

One source of speckle is random interference within multi-mode fibers; illuminating in free space or via a single-mode fiber therefore circumvents this. Incoherent sources do not exhibit speckle, so another solution is to use a LED or lamp, typically at the expense of spectral brightness. This is a common approach for total internal reflection (TIR) microscopy. Otherwise, tightly focusing and then scanning a beam effectively averages speckles out. Scanning mirrors are commercially available for this purpose, but are limited to about 10 kHz. For many imaging applications, fast scan axes are in a similar frequency range, so biasing effects are a consideration.

Conclusion

Much of the data that helps us understand biology originates as optical illumination. Concentrating light in biophotonic instruments can increase data throughput and imaging resolution. But this is limited by the physics of brightness, which is not obvious to many engineers in the life sciences. The spectral brightness of light sources, beam delivery strategies, and how to exploit built-in beam asymmetry are important considerations during the early design of such instruments.